Unlock the transformative power of the roux—a simple blend of fat and flour—and elevate your soup game. From smooth squash soups to creamy chowders and hearty gumbos, learn how to make roux and discover how this soup-maker’s secret tool adds depth, texture, and flavor, turning ordinary broths into velvety masterpieces.

In the culinary world, a roux is nothing short of magic. This seemingly simple combination of fat and flour is the hero behind some of the most delectable sauces, gravies, and — for us soup aficionados — soups.

Whether you’re concocting a creamy chowder, a hearty gumbo, or a classic French velouté, understanding the nuances of making a roux is a culinary skill every home cook should have.

But what exactly is a roux? And why is it so important in cooks’ kitchens around the world … while at the same time being a little bit intimidating? Let’s answer those questions, and break down the mystique behind this important ingredient.

What is a roux?

Pronounced ru (like too) and originating from French cuisine, a roux acts as a thickening agent, providing both structure and depth to various dishes. The darker forms of roux take on nutty flavors that form the basis for rich gravies.

A roux is simply flour and fat — e.g., butter, oil, bacon grease, lard (or sometimes stock, in the case of velouté) — stirred together over medium heat to form a paste and cooked for a length of time.

While it might seem like a mere technical step in soup-making, a well-made roux can transform a watery, lackluster broth into a velvety, rich soup that becomes the foundation of the comfort-food soups we love so much.

In soup-making, a roux is an important tool in the cook’s repertoire. It provides body and, depending on how long you cook your roux, it can also add a depth of flavor that elevates even the most basic recipes. And most importantly — to this cheese-loving soup chef, at least — a roux is the basis for rich and creamy sauces, including cheese sauces (think, mac and cheese!).

Types of roux

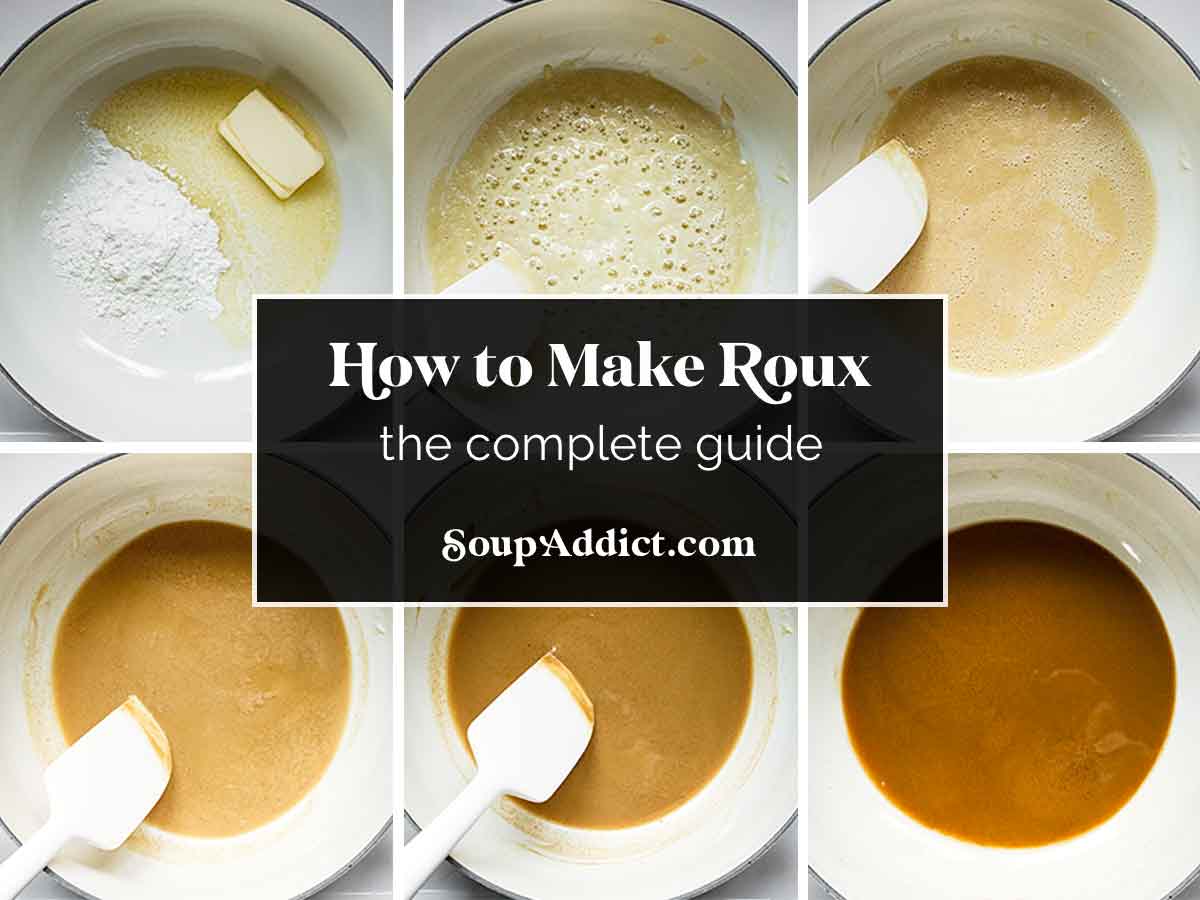

There are four basic types of roux commonly used in the home cook’s kitchen, categorized by the color of roux and its resulting qualities:

- White roux: A white roux is a pale color and is minimally cooked, just long enough to remove the raw flavor of flour. It’s used for bechamels and cheese sauces, and to thicken dishes — such as soups — to a rich consistency.

- Blonde roux: A blonde roux is cooked until the flour and butter just begin to take on color. It can be used for cheese sauces and veloutés.

- Dark roux (brown roux): A brown roux is cooked until chocolatey brown and becomes rich and nutty, almost a two-ingredient gravy. This is the roux used in classic gumbos and other Cajun and Creole dishes.

- Dry roux: A dry roux is a brown roux made of just flour (no fat) that is usually baked in the oven, rather than on the stovetop. Some cooks prefer using a dry roux because while it takes longer, the result is less likely to burn. Plus, you can store a dry roux in a container for future uses, just like flour.

The rule of thumb for choosing a roux for your recipe is that the lighter the roux, the more thickening power it provides. The darker the roux, the more flavor it provides, although somewhat less thickening power. Let’s get into the details on how to make roux.

I’d like to point out at the outset here that the time frames for creating the various colors of roux depend on a number of factors, including the heat retention and dispersion capabilities of the pan you’re using.

I’ve given timelines as a guide, but really the best tool for judging a roux is your eyes: when the roux achieves the color you’re looking for, it’s ready, regardless of the cooking time.

White Roux

White Roux, also known as “Roux Blanc,” is the lightest form of roux used as a thickening agent in various dishes. It’s made by combining equal parts of flour and fat (usually butter) and is cooked for a short duration to eliminate the raw taste of the flour but without adding any color to it.

While butter is the most common fat used in making white roux, other fats like oil, lard, or a combination can also be used depending on the flavor profile desired and dietary considerations.

How to Make a White Roux

Ingredients:

Equal parts of flour and butter/fat (e.g. 1 tablespoon of butter and 1 tablespoon of all-purpose flour).

Procedure:

- Melt the butter in a pan over medium heat.

- Once the butter has melted, add the flour to the pan.

- Stir continuously using a whisk or spatula, combining the flour and butter to form a smooth paste.

- Cook for around 3-5 minutes, stirring constantly, to get rid of the raw flavor of the flour, but don’t let it take on any color. (Note that the color of the roux will be affected by the type of fat you use, so don’t worry if your roux actually has color. In the photos below, I used a rich butter, which is reflected in the final white roux.)

Uses:

White Roux is often used as the base for sauces such as béchamel, which is one of the mother sauces in French cuisine. It is also employed in other light-colored sauces, soups, and gravies where a lighter color is preferred, valued instead for its thickening qualities.

Blonde Roux

Blonde Roux is a bit darker than white roux and is cooked for a slightly longer duration. It still retains a fairly light color, usually light tan or yellowish, and is utilized as a base for various sauces and soups.

Blonde Roux has a more developed, nuttier flavor compared to white roux due to the longer cooking time, but it’s still relatively mild, allowing it to complement a wide variety of dishes without overwhelming them.

Constant stirring is crucial when making any roux to ensure an even color and to prevent burning or lumping. The fat used can alter the flavor of the roux; butter is common, but oil or a mixture of fats can be used based on preference or dietary needs. Be mindful of the cooking time and the heat; too much of either can darken the roux more than desired.

How to Make a Blonde Roux

Ingredients:

Equal parts of flour and butter/fat (e.g. 1 tablespoon of butter and 1 tablespoon of all-purpose flour).

Procedure:

- Melt the butter in a pan over medium heat.

- Once the butter has melted, sprinkle the flour over it.

- Stir nearly continuously using a whisk or spatula, combining the flour and butter to form a lump-free paste.

- Cook for 5-8 minutes, until it achieves a light, golden-blonde color, making sure to stir constantly to prevent burning.

Uses:

Blonde Roux is commonly used for making velouté sauce, another one of the French mother sauces, which is produced by adding a light stock (fish or chicken) to the roux. It’s also suitable for other light-colored sauces and soups where a darker roux would affect the final color and flavor of the dish.

Dark Roux (or Brown Roux)

Brown Roux is deeper in color and flavor compared to both white and blonde roux. It is cooked longer, allowing it to develop a nutty, toasted flavor, making it suitable for richer, hearty dishes.

Constant stirring and attention is absolutely crucial when making dark roux to ensure even browning and to prevent it from burning, as it can easily do so due to the longer cooking time.

Due to the longer cooking time, brown roux has a richer, more pronounced flavor, with a nutty and toasted aroma. This makes it complementary to hearty, robust dishes where a stronger flavor base is desired.

How to Make a Dark Roux

Ingredients:

Equal parts of flour and fat (butter, oil, or a combination of both).

Procedure:

- Melt the butter or heat the oil in a pan over medium heat.

- Once the fat is hot, add the flour, stirring continuously to avoid lumps.

- Stir nearly continuously using a whisk or spatula, combining the flour and butter to form a lump-free paste.

- Cook the mixture for up to 30 minutes, or until it achieves a rich milk chocolate color, stirring regularly to prevent burning.

- Note a black coffee-colored roux is actually burnt — don’t try to save it; discard and start over.

Uses:

Brown Roux is typically used as the thickening base for brown sauces like Espagnole sauce, a mother sauce in classical French cuisine. It’s also ideal for gravies, stews, and gumbos where a darker color and more robust flavor are desired.

Dry Roux

A dry roux is made by toasting flour without any fat, compared to the traditional roux types above. Dry roux can serve as a thickening agent, just like traditional roux, with fewer calories but without the added flavor from the fat. It’s often used in Cajun and Creole cuisine, particularly in dishes like gumbo.

The lack of fat means that dry roux will not impart the same rich flavor and mouthfeel to dishes as traditional roux. If this is a concern, consider adding fats elsewhere in your recipe. And also, the absence of fats means that a dry roux might not disperse as easily in liquid, and vigorous whisking might be required to avoid lumps.

Dry roux can be stored for extended periods without spoiling, making it a convenient thickening agent to have on hand.

How to Make a Dry Roux

Ingredients:

All-purpose flour

Procedure:

- Preheat your oven to 350°F (180°C).

- Spread the flour evenly on a baking sheet in a thin layer.

- Place the baking sheet in the oven.

- Stir the flour every 15-20 minutes to ensure even toasting and to prevent burning.

- Continue toasting until the flour reaches a light tan to brown color, depending on your preference and the recipe’s requirement. This usually takes about 1 to 1.5 hours.

- Once the desired color is achieved, remove the baking sheet from the oven and let the flour cool completely.

- Store in an airtight container if not using immediately.

Uses:

When using dry roux, you can whisk it into hot liquid (stock, broth, etc.) until it reaches the desired thickness. Ensure that you whisk it thoroughly to prevent lumps from forming. Just like with traditional roux, the amount of dry roux needed will depend on the desired thickness of the dish.

Some cooks prefer the dry roux, but I rarely use it myself. It might be a quirk of my own oven, but I find it difficult to achieve even browning in the later stages (visible in the 4th photo above).

Roux in action here on SoupAddict

I frequently use a roux in my soups for thickening or to mix in the occasional cheese sauce. Here are a few recipes of mine that you can review and see the results:

- Cajun Mac & Cheese (an in-skillet white roux)

- Shrimp Etoufee (blonde roux)

- Chicken Seafood & Sausage Gumbo (dark roux)

- Buffalo Blue Cheese Chicken Soup (white roux as the basis for a blue cheese bechamel)

- Sheet Pan Roasted Red Pepper Tomato Soup (a unique paprika roux)

- Mac and Cheese Beer Soup (white roux)

- Mulligatawny Soup (an in-pot white roux for a thickening velouté)

I hope this post was helpful in learning how a roux can enhance your soups, and to strip away any mystery about how to make a roux. To learn more about a roux’s role in sauces, visit my post covering the differences between Roux vs. Bechamel vs. Mornay.

Happy Roux’ing and Souping!